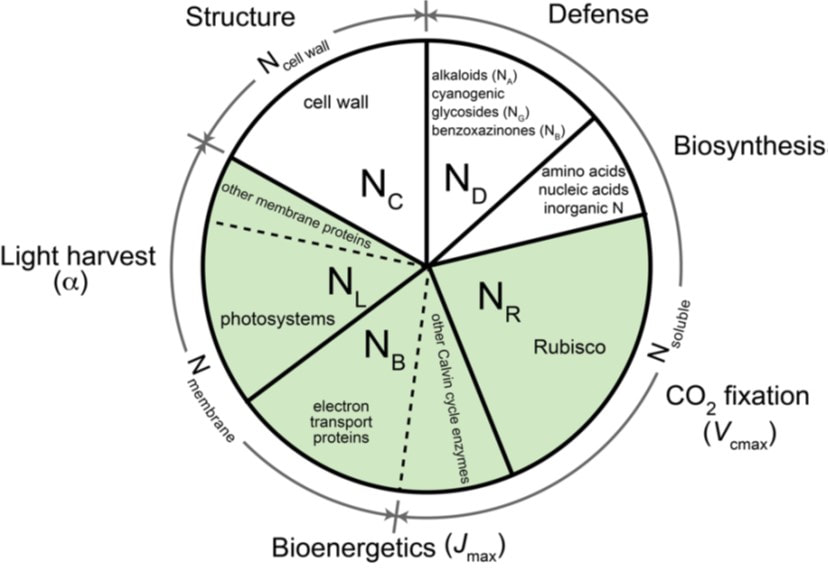

Non-native locally dominant (i.e., invasive) plants tend to have higher photosynthetic rates compared to co-occurring native plants. Variation in photosynthetic rate is often due to differences in leaf nitrogen allocation patterns, especially in temperate ecosystems. Physiological advantage in the invaded range is hypothesized to be a result of shifting resource allocation away from structure/defense (e.g. cell wall proteins and secondary metabolites) and towards photosynthetic machinery (e.g. rubisco and chlorophyll) (Figure 1). This is the premise of my postdoctoral research on comparative physiology of invasive plants in their native and invaded ranges.

Using portable infrared gas analyzers, I’ve measured photosynthetic responses to light and CO2 for populations of more than 40 species of woody and herbaceous plant invaders commonly found in temperate understory or field habitats in Japan, France, and eastern North America. In the lab, I determine the biochemical constraints of carboxylation rate and light use efficiency for these same populations via protein extractions (e.g. rubisco, chlorophyll, cell wall proteins, and secondary metabolites). The global scale of this project will allow me to test hypotheses related to pre-adaptation, if home and away populations are similar, or evolution of increased competitive advantage, if invaders shift allocation patterns in their invaded range.